For all my promises that I would be “Movie Thoughts” Girl, I have been posting a whole bunch about not movies. Sorry! Part of that is because mostly I have be watching and re-watching rubbish TV shows on Netflix Instant. Because I am cheap. And super busy. (By the way, this is Rachel, as have been the past 4 posts.)

However, it is now CHRISTMAS BREAK! This is just the best thing ever. It means that I have watched movies, specifically the new movie-fied version of the musical Les Miserables!

FIRST, (I need to get this out of the way so that my music-person soul doesn’t devour me) I was really disappointed by the singing. The exceptions to this rule were Colm Wilkinson (Bishop) briefly, Eddie Redmayne (Marius) always, Anne Hathaway (Fantine) sometimes, and Samantha Barks (Eponine) in one of her songs. Russel Crowe was better than I anticipated he would be, but my basis for comparison on the role of Javert is operatically trained baritones, the depth and warmth of whose intonation makes you want to weep when you hear them sing warm-ups. So he lost.

As for the rest, for some reason the presence of microphones and close-ups has made several people who should be able so sing for real forget that part of singing is carrying through a phrase. For those of you who are not super interested in the emotional ideas behind different techniques of singing, feel free to skip down to the bolded and underlined word “SECOND.”

As for the rest of you: part of what makes singing work is that when sustaining a note you are not “holding” a note. It isn’t your thing that you hold onto until you are done playing with it. Rather, you keep your breath, and body, and emotions so completely open that the sound can continue without you getting in the way. What this means is that you “feel” an emotion for a note in a different way than if you were to feel it normally. If you try to sing feelings exactly the way you feel them, somehow it becomes self-indulgent.When you are sad (I’m talking ugly-cry sad), you are not attempting to let others into your suffering.

That is why the tenseness, shaking, series of gasps, sighs, and hiccups make sense for that emotion in real life. However, if someone were to ugly-cry a note, while the audience might pity the performer, it is almost impossible for the audience to enter into that emotion with the performer . The point of singing is to feel things not for yourself, but in such a way as to allow other people to enter into that feeling.

This mini-treatise on singing effectively is mostly to say that the trick of “singing more naturally” or “with more rawness” that is allowed by microphones is actually terrible for conveying the original intent and emotion of the songs. Hugh Jackman, by sighing, cutting the lines off in weird places, and refusing to sustain notes that are meant to be powerful, open, and vulnerable seriously detracts from his performance. He refuses to let the audience in. What should be a painfully vulnerable moment shared with the audience becomes about Hugh Jackman and all of his feels. This is safer, less human, and ultimately less interesting.

You can see this distinction between feeling for the audience and allowing the audience to share in the feeling by comparing any of Jackman’s songs to Eddie Redmayne’s performance of “Empty Chairs at Empty Tables”. The openness, honesty and vulnerability is undeniable.

Now that I have had my little singing rant…

SECOND , this movie was so close to being faithful to considerations of Victor Hugo’s book… but they just couldn’t let it be.

Basically, the idea we are meant to examine is: How ought we, as human beings, to respond to “Les Miserables”- the miserable ones? What is the right human response to suffering? Hugo (and the creators of the musical) give us a number of alternatives, and show us the fruits of each.

1.) Marius and Cosette: The Romantic Impulse

The Romantic Impulse, which sees nothing but the beloved and seeks to simply be away and happy is absolutely a response to human misery and suffering. It is the recognition of and desire to escape suffering. This is (quite simply) a young response to misery, and there is there is a certain validity to it. It is rooted in love, that much is certain. Yet, it also results in or requires a blindness to all but the beloved. As we see in Marius and Cosette at the end of the story (once they have matured and truly opened their eyes), both are left with the realization of how much they have benefitted by the sacrifice of others. Romantic love, while it can anesthetize us to the suffering of the world, does not actually make it go away. Sooner or later, we must grow into a deeper love that allows us to do more than escape suffering.

2.) The Thernardiers: Opportunism

Oddly, this is likely the oldest human response to misery, and the hardest to eradicate. Actually, one of my favorite (and least favorite) aspects of Les Mis is that the Thernardiers keep showing up. They are like cockroaches after the bomb. Nothing kills them, and they always have a new way to take advantage of the suffering of others. Much as we may wish to ignore this aspect of humanity, Hugo does not allow us to. At the end, when idealism and justice are dead and real love is at best a miraculous memory, opportunism is alive and kicking. (Side Note: Helena Bonham-Carter and Sasha Baron Cohen were PERFECT for this!)

3.) Javert: Absolute Justice and Judgment (THE LAW)

Javert is the ubiquitous man-of-the-law. Oddly similar to Thernardiers, Javert is always there, but always in a new uniform. He is more than a legalistic man; he is The Law. He is Every Law. From jailer, to parole officer, to town constable, to Parisian officer – he is human law, which in every form aspires to divinity it its absoluteness. Except that he is also so human! When faced with suffering, misery, sin and squalor, we WANT to stand beside and become the law. The law seems safe.

My favorite parts of this movie were both of Javert’s major soliloquy songs. Both perfectly illustrate the problem of the “Absolute Judgment” approach. Each is performed with him walking along an impossibly high ledge looking out at a beautiful and cold view of a Paris night. The director, Tom Hooper, does a brilliant visual refrain in each song. As Javert sings about the perfect and unflinching justice of God, which casts men down even as He cast out Lucifer, Javert’s feet are shown teetering, barely staying on this impossibly high ledge.

Hugo uses the character of Javert illustrates the problem of perfect justice. As Javert realizes: we are imperfect. If the response to misery is justice untempered by mercy then at some point we will ALL fall. And so he does. Judgment is not enough, or rather it is too much. For a human being to attempt to maintain perfect justice is ultimately suicidal.

4.) Enjorlas and the Students: Revolution

Hugo gives us yet another young approach to suffering. Revolution. The good intention is undeniable: make the world better for the oppressed poor. However, it is not an accident that when Hugo depicts this it is a failed revolution. These passionate young students whose idealism keeps them painfully awaiting the uprising of the poor whom they defend…. they die.

This is a problem. This is a young approach to suffering, like the Romantic impulse, because it also is predicated on a sort of blindness. While the revolutionaries see all of the evil and weakness in the world in the oppressors, they are blind to the evil and weakness in the oppressed. The correct approach to human suffering cannot be blindness to its effects, or blindness to God in those who persecute. In order to respond rightly, we must see rightly every aspect and still love, give, and sacrifice – whether or not it is deserved.

This does not make the deaths of Enjorlas and the students less tragic. It does, however, make Hugo’s opinion on the Revolutionary approach to suffering more clear. Which brings us to….

5.) Jean Valjean, Fantine, Eponine, and the Bishop: Christian Charity and Self-Sacrifice

The essential differences between the students’ self-sacrifice for the people who never come, and Jean Valjean’s sacrifice and submission to Javert is this: the students EXPECT the people to rise, and they fight for that anticipated utopian ideal. Valjean expects nothing, except perhaps for follow after him and arrest him once he has been set free. Valjean performs his sacrifice with no notion of recompense. Every act of self-gift is a perfect and FREE gift. That is Christian charity.

This same charity is demonstrated in EACH of the characters listed above. I defy you to look at Fantine, Eponine, and Valjean and say that they are in any way blind to the misery that can exist in this world. Yet each gives their love unflinchingly.

Fantine, the abandoned, broken, prostitute gives her dignity, honor, and life for the future of her daughter.

Eponine, the ill-parented, unloved young girl gives her friendship, her love and her life for the future happiness of a man who does not love her back.

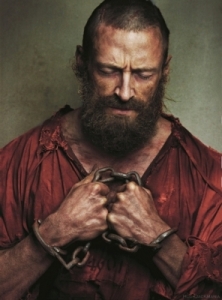

Valjean, the wrongly imprisoned,accursed, hunted convict gives his freedom, money, safety, future, EVERYTHING for everyone he meets.

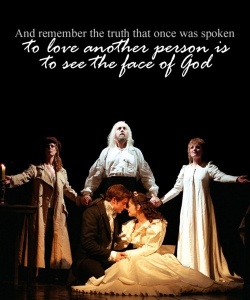

They perfectly see the corruption and misery and suffering of the world. They live it. They do not expect it to wipe it away by their individual actions. They are not so proud. Nonethe less, they give love in perfect gift and humble hope, in participation with the love of God. This perfect sacrifice and gift is why these characters make a final appearance at the end of the stage musical. They are each permitted to sing in beautiful and heavenly harmony the moral of the story:

“To love another person is to see the face of God!”

This is my gripe: the movie makers could not let that moral stand. Even before the last note of that refrain finishes echoing in the Parisian chapel where it is set, the camera zooms out to a heavenly…. BARRICADE?! On this utopian barricade that spans all Paris, the final refrain is given to the Revolutionaries, and the refrain becomes “Do you hear the people sing?”

Having seen this musical before, somehow I have never minded the refrain of “Do You Hear the People Sing?” as the finale of the show. The ghostly revolutionaries standing and marching in the background of heaven has never bothered me until now. However, the visual jump in the movie from the chapel to heaven as a barricade struck me violently with the sense that they missed the point.

The cinematographic decision to set that final song on a barricade (US AGAINST THE WORLD!) completely undercuts that message. “To love another person is the see the face of God.” That emphasis on love as seeing rightly seems to me essential, and the revolutionaries do not see rightly. They fail to see God in their adversaries. They fail to see the effects of sin and suffering in their compatriots. I absolutely believe that Victor Hugo issues a call to action. However, that action is not to battle. It is to Love – to see the face of God in other people.

This is what makes Valjean the hero: he sees God even and especially in his persecutors. If that ain’t an attempt to be like Christ, I don’t know what is.